01 Jun The artist called Fringe and the meaning of his symbols

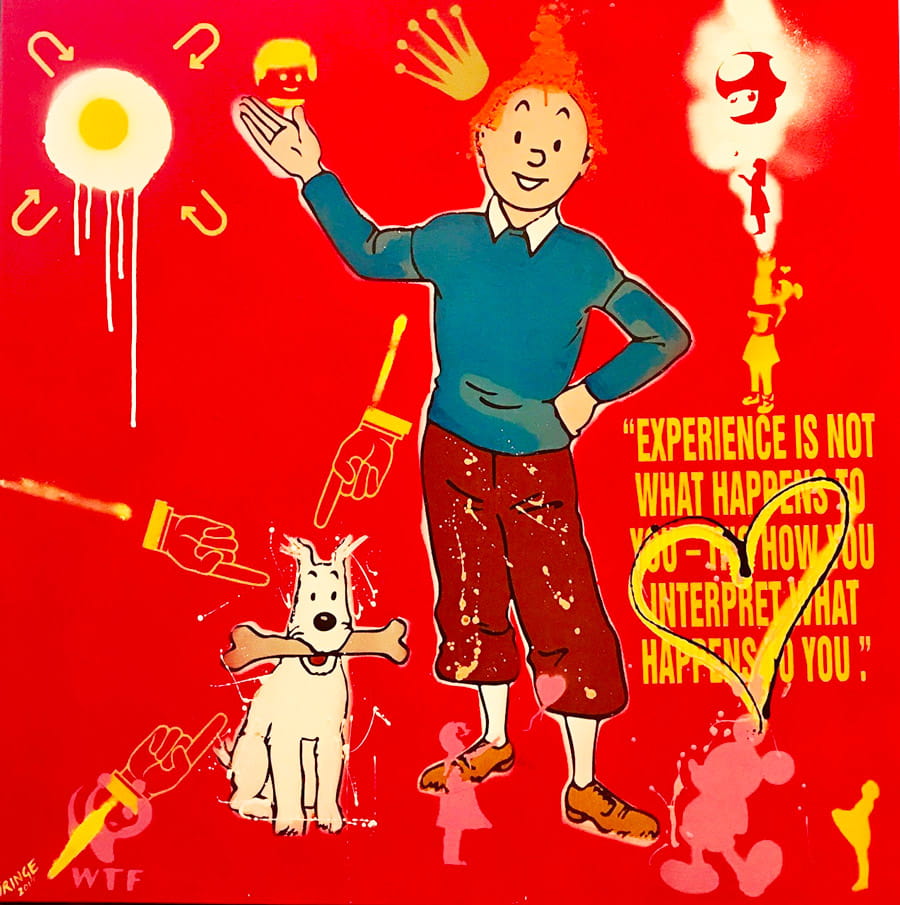

Characters: Monroe, Gandhi, Mickey Mouse, Tintin

The artist known simply as Fringe is one of the fast-rising stars working in particular idiom, in South Africa today.

The idiom is a combination of grafitti, popism and social satire. Others working working in a similar vein include Faith47 and to some degree Sindiso Nyoni. All have roots in outdoor mural art, as well as in comic book illustration elevated, at times, to the gallery context. But for Fringe his obvious playfulness points to a deeper meaning, and he works with a set cast of characters and symbols. Since he does not identify himself, and rarely conducts interviews, it’s down to us to come to conclusions about what the works mean when produced in the medium of paint and collage on canvas.

What we do know about his process, from an interview for the exhibition Fringe: The Very Definition (2017), is that his “embedded motifs,” as he calls them, point to a “constant contradiction of recognisable and spatial entities, combined with controlled and uncontrolled forces – precise versus loose – come together to convey my message.”

In other words, the famous characters he puts in his work all exist within the space of the canvas to show how our preconceived notions of who they are shifts from viewer to viewer. And from space to space. No single individual thinks of Marilyn Monroe, Mahatma Gandhi, Mickey Mouse or Tintin in a uniform way, although we all believe that these historical “characters” are so fixed in our consciousness that they mean the same thing to all of us.

At the same time, Fringe is clearly equating such towering figures as Monroe and Gandhi to two dimensional comic book characters like Mickey Mouse and Tintin.

From the start we can begin to debate what Gandhi means in the South African context, a country where he is known to have begun to think about his journey towards passive resistance. The figure of Gandhi is not without controversy though, and many consider him to have had negative views on Black Africans at the time of his protests against British colonialism. Similarly, the well-loved character of Tintin is considered by many outside of the Western culture to have been brazenly neo-colonialist.

The humorous and deceptively happy paintings of Fringe encourage us to question these characters that have become like brands in our pop culture (of course, the artist began his career in advertising so an understanding of branding is part of his creative DNA). Is the figure of Monroe, for example, really still the ideal woman in a world that is hotly discussing gender, powerlessness and objectification? Or is she, now, considered a bad example of how women should “be”?

Symbols: World Wildlife Fund, Coca-Cola, fried egg

The symbols Fringe employs are no less intriguing or controversial, and this is where his social satire really kicks in. The logo of the revered World Wildlife Fund is redesigned to incorporate WTF (What The Fuck) and Coca-Cola is redesigned to read “Cocaine”. It’s down to us to decide whether these revised slogans are deserved.

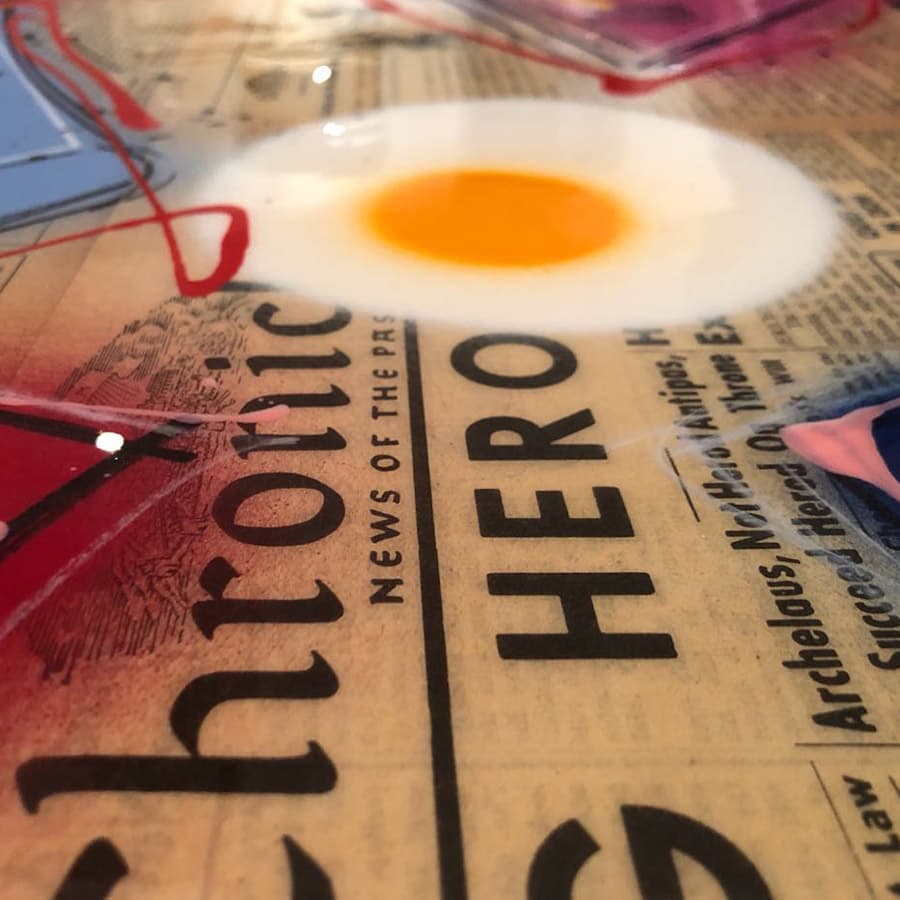

In a similar but more intriguing way, the ubiquitous fried egg in the paintings of Fringe is not merely a decorative touch.

In his earlier works the artist replicated Leonardo da Vinci’s study of the fetus as found motif that formed a historical centerpiece in compositions of more modern characters and symbols. The developing child (and one of the most recognizable in art), we can assume would someday become the individual that would have to find a place in a world of established brands and historical icons.

Likewise, the egg is a symbol of development and nourishment. But it’s not, entirely, a clearly defined symbol of positivity and healthiness.

The fried egg is produced perfectly in its two-colour spray paint technique. The white paint, dripping randomly, replicates the actual cooking technique. But the fried egg is also a slightly sad symbol of mass produced breakfasts at fast food chains and franchises.

We cannot look at it without automatically thinking of its place in our popular food culture, where quick fix, cheap meals are the products of gigantic industries that are, today, being accused of playing havoc with the future of the planet.

Matthew Krouse works for the Daville Baillie Gallery that represents the work of Fringe the artist. From 1998 to 2014 he was arts editor of the Mail & Guardian newspaper. He is the editor of the book Positions: Contemporary art from South Africa (Steidl, Germany)